A bribe for the wealthy to move to, or remain in, the UK

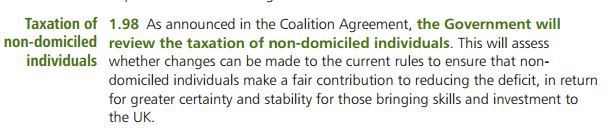

Late February. How's your New Year's Resolution going? Not so well? Congratulations, you possess a necessary (but happily for George, not sufficient) qualification to be the next Chancellor of the Exchequer. In its first Budget, 22 June 2010, this is what the Coalition said:

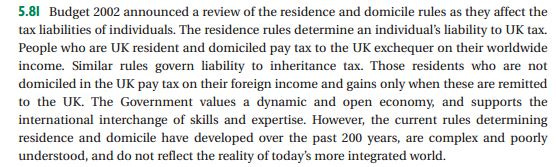

But am I making some party political point? I am not. This is what Labour said in its Pre-Budget report 2002:

And these are but the last two in a long line of failed resolutions: changes were considered in 1994, 1988 and... There have been some reforms: Labour introduced a levy for non-doms: a £30,000 annual membership fee to belong to the best tax mitigation club there is. And the Tories have changed the fee structure to reflect the (perfectly sensible) notion that the less deserving you are of club membership, the more you should have to pay to continue to belong. Come April, if you've been resident in the UK for 17 of the last 20 years, it will cost you £90,000. But proper reform? It's the fiscal equivalent of getting a little more exercise. You know it's a good thing but it's just... so... well... Gosh, is that the time? There's an election coming!

***

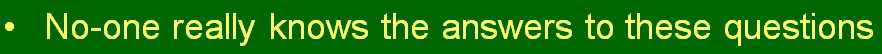

What most proper (by which I mean non-tax haven) countries say is: if you live here we'll charge you to tax on all your income and gains around the world. In the UK, we've carved out an exception to that rule: if you are not 'domiciled' here we'll charge you tax only on the income or gains you bring in (or 'remit' - hence the remittance basis) to the UK. Your assets and income outside the UK won't be charged to tax here - and, if you arrange your affairs carefully, might not be charged to tax anywhere. And your country of "domicile"? That's your 'home' country. I could write tens of thousands of words delineating the operation of these two key concepts: 'domicile' and 'remittance' basis. But to focus on how they work rather than what they accomplish is to miss the point. And the point is that the remittance basis is a fiscal sweetener - a bribe, if you like - payable to the wealthy with foreign connections to cause them to move to or remain in the United Kingdom. It's only having called it by name that we can turn to look at whether we should be paying it and, if we should, what it should look like. Proponents of the non-dom rule say that it encourages wealthy foreigners to move to (they don't say but do mean) London and spend their money in (also) London - and that brings benefits including additional tax receipts to the economy. They're right. Detractors say, looked at globally, the rule signals our enthusiastic participation in a race to the fiscal bottom which makes winners of the fantastically wealthy and losers of everyone else. They're also right. Some detractors - a good recent example being the BBC's recent The Super Rich and Us - also point to the fact that the arrival of wealthy foreigners hasn't spelled the end for inequality in the UK. Someone, somewhere, possibly in Norfolk, will be flexing his blackboard ruler, but that seems to me a little like arguing that, because I've turned on my two-bar electric heater and I'm still cold, it follows that heaters don't make you warmer. But just stand back and accept the logic of the (good) points for a second. There are all sorts of ways in which we might entice wealthy foreigners to come and live here. Stable government, a civil service free of corruption, our cultural richness, excellent public infrastructure (someone stop me, please, before I get completely carried away). Do we need a fiscal inducement too? And if we do need a fiscal inducement is this the one? To answer that question we'd need to model how many would leave, how many would fail to come, and what the loss would be to the economy. Many will tell you they can, or have, performed this exercise. For myself, I like to recall what the Institute of Fiscal Studies, which so often (and often accurately) tilts at fiscal forecasting had to say, back in 2007, about the effects of rival political proposals for a non-dom levy:

This is the link for that pleasing flash of intellectual clarity. But let's press on, whilst recognising that to do so we'll need to assume that sensible modelling is possible. Let's also assume (controversially, but for the sake of argument) that we'd like to continue paying a sweetener. The question then is, what should that sweetener look like? To answer that, you need to go back to my two key concepts: remittance and domicile. The concept of domicile has many problems. The question whether X is domiciled in the UK often fails to admit of a clear answer: it is to borrow an attractive phrase (from Ian Jack) "a peculiar mixture of fact and intent". Perhaps in consequence, legal challenges to domicile status are relatively rare (such that questions might sensibly be asked about whether all of those claiming the status actually have it). But most importantly of all, the line in the sand that the legal test draws is a pretty crappy way of separating out those we might want to give a sweetener to and those we might not. You might think that, after someone has put down roots, they might no longer need (or deserve) an incentive to come or remain here? But the domicile rule all but ignores that critical fact. As to the remittance basis of taxation, it's enormously complex to apply. That's a thing modestly undesirable (to all but tax advisers). But its real failing is that it disincentivises the very thing we want to incentivise. The reason we give a sweetener to get wealthy foreigners to come here is not because we like their company (although often we do). The reason is that we want them to bring their money here and spend it here. Taxing them on the income and gains that they bring into the country discourages them from doing the very thing that the sweetener is designed to encourage them to do. I don't want to suggest policy on the hoof (he said, with the inevitable air of a man about to do so anyway). But it doesn't take much imagination to think of mechanisms that might consistently promote the policy objective of offering a sweetener. If we are to have a tax mitigation club, what about a different one, with equally high annual subs, but that gave you a reduced rate of income tax or capital gains tax for the first, say, five or ten years of residence here? Not desperately politically palatable perhaps, but no less so than the present system properly understood, and likely to deliver far better economic results. More modest reform might look like a domicile equivalent of the statutory residence test in the Finance Act 2013 - to create bright line tests between resident and non-resident status - coupled with a deemed domicile provision (akin to that in the Inheritance Tax Act 1984) by which you would be deemed to be a UK domiciliary after a number of years residing here. But I'd love to hear your suggestions - and responses to the above - too.