A further note - on Real Facebook's Accounts

The release by UK Facebook of its accounts made some media noise. Heather Stewart of the Guardian covered them here, Richard Murphy here, Vanessa Houlder here, Hugo Rifkind here and your present correspondent observed that UK Facebook was unlikely ever to make a, or a material, taxable profit here. Most - with a couple of honorable exceptions - of the twitter taxperts rallied round UK Facebook. A number of bad points were taken in its defence - and no doubt one or two good ones as well. I would not want to pretend - for it is a long mile from true - that I have any monopoly on insight. It does surprise me that this is the invariable and knee-jerk reaction to stories asking whether Big Business is misbehaving. Although not quite as much as it surprises me that many taxperts don't understand that the consequence of their myopia is poor understand of tax issues: journalists don't feel able to call on experts that they can't trust to tell the unvarnished truth. This is a real bugbear of mine: I've written about it (in two addresses to my colleagues) here and here. As I put it in the first of those two posts:

Here's a short prescription. Rather than bemoaning the limited understanding of public and media, we should work to improve it. I speak to a lot of journalists - several a day - and I've only ever spoken to one who wasn't interested in the truth. But we need to be transparent about the premise from which we proceed. When we act in a professional capacity it's right that we talk our own book. Everyone understands that we sometimes speak as lobbyists. But it's important to signal when we do. Otherwise we become part of the problem. If we merely stand on the sidelines and criticise, we don't merely ignore Gandhi's injunction to 'Be the change you wish to see in the world.' We thwart it.

***

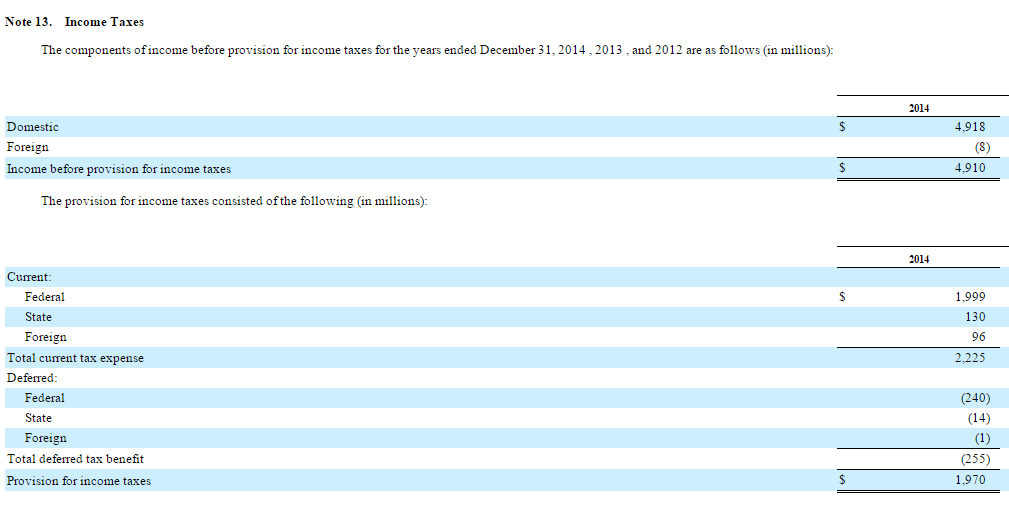

Anyway, on to UK Facebook. One of two points taken in its defence was that you can tell that there is no funny business in its accounts because if you look at the rate of corporation tax paid by Real Facebook on its global profits that rate is really rather high. If true this is a decent point: why would you shift profits out of the UK and into another jurisdiction where you'd pay as high or an even higher rate of corporation tax? But is it true? Well, at first glance, it looks true. Annex 2A of this document, prepared by the EU Commission, states that Real Facebook paid 45.5% tax on income in 2013. And if you go to Facebook's own accounts, at Note 13 you find this (and I should note that the accounts refers to income tax which is what our American cousins call corporation tax. For ease of use for my UK readers I am going to call it US corporation tax) :

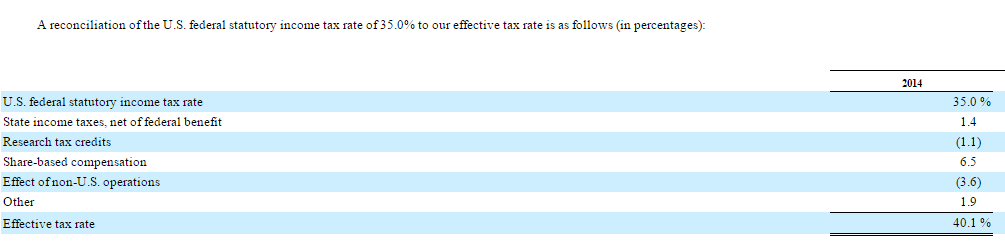

And this:

They're probably too small to read on the bus but what they show is that in 2014, Real Facebook made provision for $1.97bn of US corporation tax, an effective tax rate of 40.1% on worldwide income. In 2013, the equivalent rate was 45.5% (hence the Commission figure) and in 2012 it was a remarkable 89.3%! This surprised me a little because, as the Note itself records, the statutory rate of US corporation tax is 35%. And few of us tax professionals are paid to increase above the statutory rate the amount of tax our clients pay. So I did a little digging. Not that much, mind. Further down in the very same note you find this:

Excess tax benefits associated with stock option exercises and other equity awards are credited to stockholders' equity. The income tax benefits resulting from stock awards that were credited to stockholders' equity were $1.85 billion, $602 million and $1.03 billion for the years ended December 31, 2014, 2013, and 2012, respectively.

So alongside the US corporation tax paid, Real Facebook also received what are shyly described as "income tax benefits" arising from share options (I'll talk about share options for shorthand although there will be other share based remuneration too) it had granted, of £1.85bn. Hang on a second: so is the tax provided for by Real Facebook in 2014 $1.97bn (at an effective tax rate of 40.1%) or $1.97bn minus 1.85bn (at an effective tax rate of 6%)? To find the answer to that question, you need to dig a little deeper. At page 42 you find this:

2014 Compared to 2013. Our provision for income taxes in 2014 increased $716 million, or 57%, compared to 2013, primarily due to an increase in income before provision for income taxes. Our effective tax rate differs from the statutory rate due to non-deductible share-based compensation, operations in jurisdictions with tax rates lower than the U.S., and tax research credits. Our effective tax rate decreased primarily due to a change in our geographic mix of pre-tax income.

The bit that's emboldened in that quote was emboldened by me. Now I am not an expert in US Accounting Practice or the US Tax Code. But my understanding is that under US Accounting Practice (and the same is true here) an employer get an accounting deduction when it grants most common types of share option based remuneration to employees to reflect the fact that its incurred expenditure. But under the US Tax Code it doesn't get a tax deduction when it grants those options; instead it gets that tax deduction later on when the options are exercised. And the amount of the deduction depends on how much the option is then worth. This timing mismatch has a number of consequences. But in particular, it means that a business with substantial staff costs which costs it chooses to meet in the form of share options will always show a high rate of US corporation tax.

Example. Assume for the sake of example that in 2014 I have income of 100, staff costs of 90 all of which I meet by granting share options of that value, no other costs and the rate of corporation tax is 35%. I will have accounting profits of 10, taxable profits of 100, I will pay tax of 35 and I will have an effective rate of corporation tax of 350%.

But, of course, in the real world, you can't ignore that, in the future, when those share options are exercised, you will get a tax benefit.

Assume that the options in Example were all exercised on 1 January 2015 at a price which reflected my expectation of their value at the date in 2014 when I granted them. I'd then receive a tax benefit of 35% of 90 or 31.5. That tax benefit would be attributable to my activities in 2014. And if you matched it to 2014 I would have paid tax on my 2014 activities of 35-31.5+ 3.5 and my effective tax rate would be 3.5 on 10 or 35%.

Of course, in practice it's a little more complicated than this example implies. In 2014 we would show on our balance sheet an expectation of what tax benefit we expect to get in the future (an item called a deferred tax asset) which we would adjust upwards or downwards depending on how closely actuality delivered on our expectations (perfectly in my example, less so in practice). And the tax benefit we got might not be attributable only to our activities in the year in which we got it (it is in my example) but in earlier years too. But these complexities shouldn't obscure the fact that the tax benefit derives from our activities and reduces the amount we have to pay to the tax authority. In 2014, Real Facebook made an upward adjustment to its deferred tax assets attributable to stock options of $1.85bn. That figure is not wholly attributable to Facebook's activities in 2014. But it does reflect share options granted by Real Facebook to its employees - which is a cost of Real Facebook doing business. And it does reflect a 2014 upwards adjustment to Real Facebook's expectation of tax benefits arising from the grant of those share options. And you can't ignore it and pretend it has nothing to with Real Facebook's real US corporation tax liability. And if you match it to Real Facebook's actual provision for US corporation tax in 2014 it drives Facebook's effective tax rate down from (an improbably high) 40.1% to (a less surprising, for us cynics at least) 6%. And the argument that you can tell that there's no funny business in UK Facebook's accounts because of the high rate of corporation tax paid by Real Facebook simply evaporates.

***

I said there were two arguments advanced by the taxperts in UK Facebook's defence. The other is the total tax contribution argument. It is that you shouldn't focus on the corporation tax paid (or more accurately not paid) by UK Facebook because of all of the other taxes that UK Facebook causes to be paid. In my original piece on UK Facebook's accounts I said of it this:

The commentariat didn't think there was any of that going on. Here, by way of example, was one response from a commentator:

I can’t imagine anyone would seek to excuse legal non-compliance in one area by saying ‘but they comply with some other law’...

It's worth pausing to note that I was making a general observation about how tax avoidance is justified. And that justification certainly is advanced. Speaking yesterday of UK Facebook here Chas Roy-Chowdhury, head of taxation at the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, said this:

This is, it seems to me, a diversion. The allegation that someone has avoided corporation tax does not seem to me to be answered by pointing to the fact that they comply with other of their legal obligations. [twitter-follow screen_name='jolyonmaugham']