How much will it cost us to cut the top rate of tax?

Earlier this week, George Osborne came close to suggesting that by cutting the top rate of tax from 50% to 45% he had increased tax revenues by £8bn. The relationship between that suggestion and the truth is a distant one as I explained here. Its evident falsity does not, however, make it any less convenient to those whose constituencies, or pocket-books, would benefit from further cuts. And so, predictably, it has precipitated a number of calls for those further cuts - perhaps in the coming Budget. It is, unfortunately, recondite in these times to want to make policy by reference to the evidence rather than the heroic assertion of that which is convenient. Be that as it may, here's some evidence: about who it is who pays the top rate of income tax; how much they benefit from cutting it; and how much it costs the public finances to make that cut. In this tax year, about 332,000 people will pay the 45% "Additional Rate" of income tax. That's about half a percent of the population. About 83.5% of them are male. More than 332,000 people earn more than £150,000 per annum - the earnings level at which you begin to pay the top rate - but the tax system offers reliefs to reduce your taxable income, and these reliefs are overwhelmingly accessed by higher earners, as I showed here. The mean average earnings of someone in the Additional Rate category of earner is a bit over £400,000 pa. That means that more than half of the income of that mean earner is taxed at the Additional Rate. If you are one of the 16,000 people earning over £1,000,000 pa, your mean average earnings of £2.43m pa means that virtually all of your income is taxed at the Additional Rate. If you earn £2.43m, a cut of 5% in the top rate of tax will give you an extra £120,000 in your pocket every year. In total, Additional Rate payers will pay a bit over £30bn in income tax this year. So if you cut the Additional Rate from 45% to 40% you will give them, collectively, a tax break of more than £3.3bn. This won't, however, cut what Government receives by £3.3bn. Most people aren't keen to pay tax and when we raise income tax rates we increase the incentive to find ways to avoid that increased burden - either by engaging in tax avoidance, or by retiring early, or working less or leaving the country. When people give up work or work less or emigrate they don't just avoid the increase in the rate of tax, we also lose the rest of the tax that they pay. So there are reasons to be cautious about raising rates of tax. But, of course, people who are highly motivated by tax rates tend to live in low tax jurisdictions - they are not in the UK in the first place. As the FT put it earlier this week:

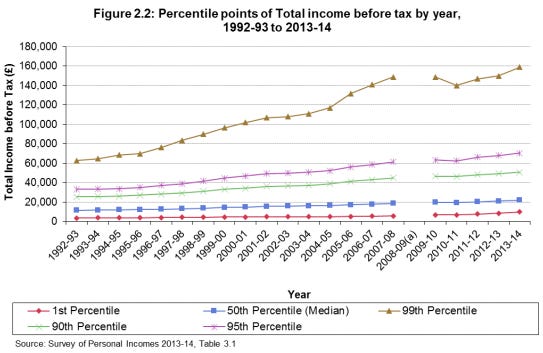

These considerations also act in reverse. When you cut tax rates you can decrease people's desire to avoid tax, you can increase their inclination to work or work on, and to move to the UK. We typically call this relationship between the tax take and changes in rates the Laffer Curve. But, as I've written here, calling it 'the' Laffer Curve is a misnomer because there isn't only one Laffer Curve - there are different curves for different taxes, at different times and in different economies. And the shape of the curve is affected by a huge number of variables including, in particular, how easy it is to avoid tax. Back in March 2012, George Osborne announced that he would reverse Labour's decision to increase the top rate of tax to 50% with effect from 6 April 2013. At the same time as making that announcement HMRC released a paper called 'The Exchequer Effect of the 50 per cent additional rate of income tax.' That paper is the only public study of which I am aware into the effects of increasing or decreasing the top rate of income tax in the UK. It concluded that cutting the rate from 50% to 45% would cost around £100m per annum. However, there is no room for doubt but that cutting the top rate from 45% to 40% would be considerable more expensive. First, our inclination to alter our behaviour as tax rates change is dynamic. The lower the top rate, the weaker the incentive to change behaviour to avoid it. You can tell this is so because otherwise, by cutting rates to zero, we would raise more than the £163bn we presently receive in income tax. Plainly this is not so. So a cut to a lower top rate (45% to 40%) will cost more money than a cut to a higher one (50% to 45%) - even where exactly the same people are affected. Second, the Coalition had marked success in tackling personal tax avoidance. One of the arguments as to why cutting rates will not lead to a reduction in tax receipts is that the incentive to avoid tax will weaken. But if it is already extremely difficult for high earners to avoid tax, it cannot sensibly be argued that diminished incentive will have a marked effect. Third, pay growth in the top percentile of earners - roughly equivalent to those who pay income tax - is strong as this HMRC chart shows:

The number of those earning above £150,000 is projected to grow by 6.5% from 2014-15 to 2015-16 alone. And the aggregate taxable earnings of that group will grow by over 6% (both calculations from data here). As more income becomes subject to that top rate of tax the cost of cutting it increases. Writing in the Telegraph last week Fraser Nelson said this:

The top rate of tax is, today, 45p but it was 40p throughout the Labour years. And for good reason: it was the optimal rate, taking the most from the highest-paid. If Osborne were to restore the 40p rate, he’d squeeze far more tax from rich and again demonstrate Conservatism in action.

Now, this is heroic asserting by Fraser. But, if you have regard to the actual evidence, there isn't room for serious doubt about the effects. Cutting the top rate of tax will deliver to the top 0.5% of earners a tax cut worth £3.3bn. And it will cost the Exchequer very considerable sums of money. My opinion is that these sums are more likely to be counted in the billions rather than hundreds of millions per annum. [twitter-follow screen_name='jolyonmaugham']