Why are we rowing about the Oxfam statistics?

On Monday, Oxfam published a report entitled 'An Economy for the 1%: how privilege and power in the economy drive extreme inequality and how this can be stopped.' And, as you'll know, the statistical foundation of that report was rather roughly handled by a number of commentators, often those on the right of the political spectrum.

I don't write to throw my Casio calculator into that ring. But to make the point I want to I need to start with a few short observations about what those criticisms identified and ignored.

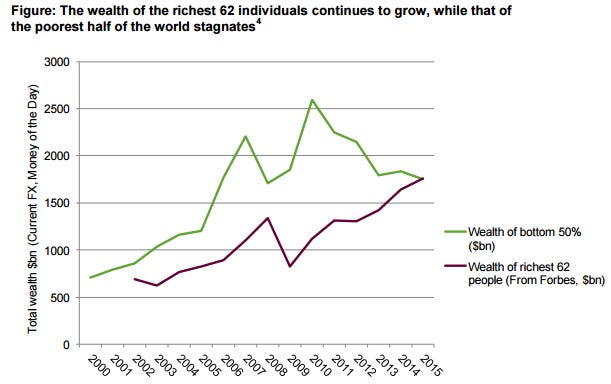

They focused on the green line in the Oxfam chart below. And often on the number of high consuming but indebted individuals in the West who you might not readily identify as poor. As Tim Harford put it:

here’s a surreal image of my own: my toddler controls more wealth than the poorest one and a half billion people on the planet.

Does he have a rich uncle?

No, but he has no debts. That puts his wealth at zero. But why should an increase in the number of net indebted individuals contributing to the shrinking wealth of the bottom 50% not be a cause for concern?

Little or no exception was taken by commentators to Oxfam's purple line - which shows a more than doubling of the wealth of the world's 62 richest people in the last six years. And most of us will shift uneasily in our chairs at this, too.

So the rough handling - although usually accurate in its own terms - often obscured, and sometimes seemed wilfully to obscure, matters that on any view we should be concerned about.

But perhaps hostility to the Report was rather predictable?

Many appear to have read it as an attack on capitalism. And the belief that capitalism possesses a unique ability to rescue people from poverty is a sacred tenet for many. Sacred - and not without evidential support as Fraser Nelson has pointed out here.

(A short aside. There important limitations to Fraser's charts too: a steep decline in the number of people with an income of less than $1.90 a day certainly tells us something about poverty - but the 'what' is rather context specific. Do you live in Malawi or Monaco? Certainly the suggestion made by the graph that the "Share of the world's population living in poverty" has declined is not made out by the data given. And, similarly, an increase in resource flows tell us nothing about who receives them. You might well expect the 'Private' flows that Fraser champions to fill different pockets to those of the 'Official Development Assistance' flows.)

Even so. Let's make an assumption I readily make: that capitalism is a powerful force for good. And look at where it should and shouldn't lead us.

It should lead us to protect capitalism - and celebrate its successes. But it shouldn't lead us to conclude that capitalism cannot function better. If any of us are sanguine about environmental change, or inequality, or abuses of the tax system, or poverty, or air pollution - if any of us are, we shouldn't be.

In fact, Oxfam's report doesn't attack capitalism. What it does do is call for changes to the way capitalism functions. A good defence of capitalism involves championing the successes but also searching out the ways that will cause it to succeed better at the only metric that matters: the health of our society. A bad defence focuses exclusively on the successes; ignores the failures; and attacks those who point them out.

That bad defence does not seek to persuade the undecideds. It has no broader ambition than preaching to those already in the choir seats. But it needs to do more. Because capitalism's friends - amongst whose number I count myself - mustn't be complacent.

There is hunger for political and economic change. In the US a fight for the Presidency between Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders is now a live possibility. And in the UK, today's complacency might quickly fall away were Labour to choose a more adept leader from its Left - especially if the public were to be exposed to another 2008 style market failure. By failing to agitate for its better functioning, capitalism's champions jeopardise that which they seek to protect.

And, perhaps even more importantly, they eschew the opportunity to advance the better world we would all like to see.